The Common Law

”The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics...

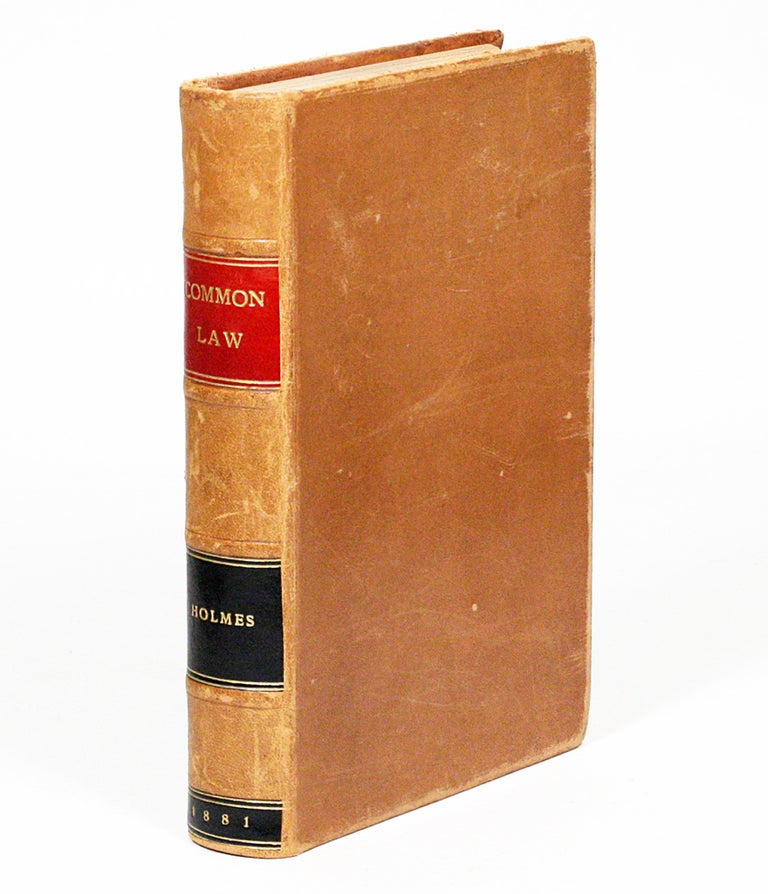

FIRST EDITION, FIRST ISSUE IN ORIGINAL PUBLISHER’S SHEEP BINDING OF “THE GREATEST WORK OF AMERICAN LEGAL SCHOLARSHIP.”.

The Common Law “is filled with novel insights and vivid imagery. Holmes’s break with the a priori reasoning of the past is announced in the famous opening sentence: ‘The life of the law has not been logic, but experience.’ Despite its flaws, The Common Law has been called the greatest work of American legal scholarship. The central insight is that rules of behavior are not the fundamental data of law. Rather, law must be understood as a set of choices, often for unstated reasons, between possible outcomes.

“In his earlier work, Holmes had labored unsuccessfully, like his predecessors, to untangle the dense mass of rules established by courts and legislature. In his first scholarly writings he had not been able to make a persuasive case for order or logic in this tangle of rules. In 1880, however, he had hit upon a new organizing principle. In cases of private law—suits for damages—judges decided which of the two parties would bear the burden of an injury. Holmes saw that the judge often found it easier to decide between the parties than to give a clear explanation or rule. The judge’s written opinion, purportedly applying a rule, was often no more than a rationalization to explain the decision arrived at on other, sometimes unconscious, grounds. Instead of searching for preexisting principles of natural right or duty, therefore, Holmes turned his attention to the decisions of judges in particular circumstances. He argued that one could generalize from past decisions to predict the future behavior of judges. These empirical generalizations from the data of judicial behavior could be stated as rules or principles of law: ‘a legal duty so called is nothing but a prediction that if a man does or omits certain things he will be made to suffer in this or that way by judgment of the Court. . . . A man who cares nothing for an ethical rule . . . is likely nevertheless to care a good deal to avoid being made to pay money, and will want to keep out of jail if he can’ (‘The Path of the Law’). Holmes believed that, even when they contradicted a judge’s self-justifying explanation, generalizations based on judges’ behavior were the true principles of law and the basis on which the study of law could be made a science. Applying his new method, Holmes thought he had discovered a general organizing principle: modern judges would impose liability on a defendant when his or her conduct resulted in harm that an ordinary person would have foreseen. The injury and not the breach of a rule of conduct was the judge’s central motive. Judges usually imposed liability on the blameworthy party, who in the modern world was the one who had caused foreseeable harm without adequate justification and who accordingly was felt to be responsible for the damage.

“In The Common Law, Holmes traces the evolution of this principle of liability through the history of the law. Law, he argues, began as a substitute for private vengeance, as a means of controlling blood feuds. It then evolved into the instrument of a more highly civilized and complex moral system, in which punishment was imposed for moral culpability. As law continued to evolve in the nineteenth century, it was tending toward reliance on a single ‘external standard’ that restricted personal liberty only to the extent necessary to prevent foreseeable harms. This evolution was driven by Malthusian forces. Only decisions that had contributed to the survival of the race would be preserved. It followed that law concerned itself solely with material aims and that law would continue to evolve until it was a fully self-conscious instrument of social purpose. The principles of a liberal, utilitarian policy of individual liberty and economic efficiency that Holmes found to be the often unstated motive of judicial opinions presumably had been favored by natural selection. Holmes’s book itself, he plainly believed, was an important step in the evolution of the law toward self-awareness.

“Although this theory of evolution through race and class struggle in which Holmes believed is now discredited, his turn toward the motives and actions of judges and away from formalistic rules of law marked an epoch that continues. Holmes’s new methodology had a profound influence. He was considered one of the founders of sociological jurisprudence in Great Britain and the United States, of the school of legal realism that succeeded it, and still more recently of studies of law employing the tools of economics and rational choice analysis” (American National Biography). Grolier 100 Influential American Books, #84.

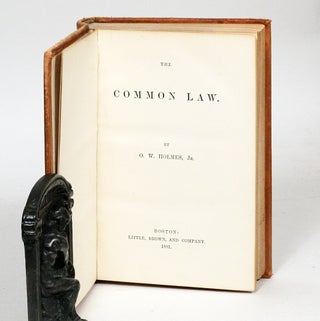

First issue, with printer's imprint ("University Press: / John Wilson and Son, Cambridge.”) on back of title page.

Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1881. Octavo, original full publisher’s sheep with later leather labels. Light general wear to sheep, first three leaves starting to split at gutter, but holding. A beautiful copy, rare in the publisher’s sheep.

Check Availability:

P: 212.326.8907

E: info@manhattanrarebooks.com