Constitution of the New England Anti-Slavery Society (1832). WITH: Declaration of the Anti-Slavery Convention Assembled in Philadelphia, December 4, 1833 (1833)

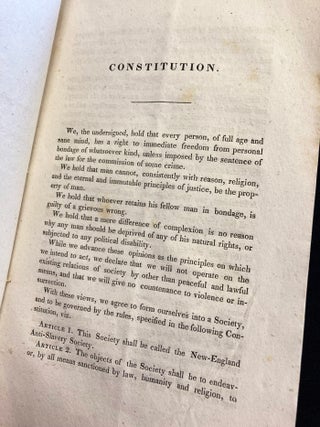

“We are, from principle, opposed to Slavery. We believe, too, that such a spirit becomes the very genius of our country. The whole American people ought to be an Anti-Slavery Society. This is the very principle upon which our government is built. The spirit of civil and religious liberty requires it. The Declaration of ’76 requires it. The spirit and letter of our Constitution requires it.”

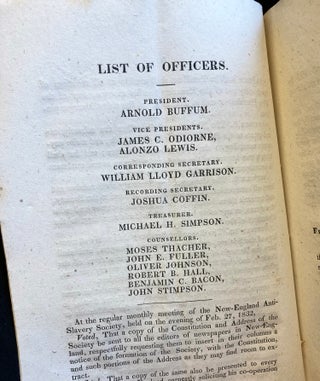

– Arnold Buffun and William Lloyd Garrison, “Address”, Constitution of the New England Anti-Slavery Society, p. 8

VERY RARE FIRST PRINTINGS OF THE CONSTITUTION AND DECLARATION OF AMERICA’S FIRST SOCIETIES TO PROMOTE THE IMMEDIATE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY.

By the first half of the nineteenth century, abolitionism in America was gaining traction in the nation’s public conscious. As a movement, organised abolition groups were propelled in particular by Quaker and evangelical communities, who highlighted the fundamentally un-Christian nature of slavery. It is from these roots that the New England Anti-Slavery Society (NEASS), America’s first immediatist society, emerged in 1832. Organising a national Anti-Slavery Convention the following year, the early forum for anti-slavery activists advocated in the strongest terms for the total abolition of slavery in all states.

Adopting the term from British anti-slavery activists, NEASS and the Anti-Slavery Convention pushed for Immediatism, which “however variously it was interpreted by American reformers, condemned slavery as a national sin, called for emancipation at the earliest possible moment, and proposed schemes for incorporating the freedmen into American society” (Thomas, p. 132). Hoping to follow in the footsteps of the United Kingdom, where the sale of slaves had been illegal on a national level since 1807 and where slave ownership would be abolished in 1833, the chief founders of NEASS, William Lloyd Garrison and Arnold Buffun, wished to see the measures that had been ratified across New England on a state-level between 1777 and 1804 enacted in the southern centres of the American slave trade. But even among the period’s most staunch abolitionists, there were debates on how to accomplish this goal.

On one hand there were those such as Horace Greeley, founder of the New York Tribune who by the 1850s would earn the reputation of an “ultra-Abolitionist”, as he was labelled in a speech to the American Anti-Slavery Society, and at the outbreak of the Civil War would propagate the controversial notion that the fast way to abolish slavery in the Union would be, in his words, “letting them go in peace”, i.e., allowing the South to secede without conflict (Higginson, p. 4; Seitz, p. 190). Rather, Garrison—who operated the Liberator, “which became known as the most uncompromising of American antislavery journals”—and the NEASS were consistently Unionist in their approach (Thomas, p. x). The first edition of the Liberator heralds Garrison’s promise of “a new era in the American anti-slavery movement, in which he defiantly proclaims, “I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation… I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD” (Arkin, p. 75; Garrison). In addition to his columns in news media, Garrison’s voice rings clearly though these two, formal documents—the Constitution of the NEASS and the Declaration of the Anti-Slavery Convention—which represent a nexus of abolitionism and freedom of the press in nineteenth-century America.

Organised largely by the NEASS and welcoming delegations from Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Ohio (as enumerated on p. 8 of the Declaration)—an amalgamation which gestures towards the social and political cleavage which would come to a breaking point in the years leading up to the Civil War—the first national Anti-Slavery Convention, held in Philadelphia from 4 to 6 December, 1833, recognised the constitutional difficulty of implementing formal change on a federal level. It states:

“We fully and unanimously recognize the sovereignty of each State, to legislate exclusively on the subject of slavery which is tolerated within its limits; we concede that Congress, under the present national compact, has no right to interfere with any of the slave States, in relation to this momentous subject.” (Declaration, p. 6)

The approach witnessed in these two founding documents was thus one of attempting to install a normative shift across the nation—with the Declaration of the Anti-Slavery Convention seeking to form both a “National Anti-Slavery Society” (Declaration, p. 1) as well as partner societies ‘in every city, town and village of our land” (Declaration, p. 7).

To accomplish this, Garrson and Buffun invoke America’s own founding documents written only decades prior, in a joint address printed in tandem with the NEASS Constitution. They aver that the letter and spirit of the “Declaration of ’76” make plain slavery’s intrinsic incompatibility with the cardinal American value “that all men are created equal” (original emphasis). To this effect, a seemingly innocuous footnote amends a reference to people of colour to make clear that “We believe that every colored person, who is either born in this country, or forced to make this the place of his residence, is as really an American, as any white-born citizen of New-England”. Furthermore, they note how such an intervention into how the Declaration of Independence is interpreted—that is, acknowledging and acting upon vital improvements to the nation—distinctly echoes the US Constitution’s own dedication to continually forming a more perfect Union.

These documents, remarkably offered here together, capture an intense image of extreme abolitionist sentiment in America. These aspirations for the nation would escalate to war within the lives of both Garrison and Greeley—figures who were to became some of the greatest influences on Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation.

References:

Marc M. Arkin, “The Federalist Trope: Power and Passion in Abolitionist Rhetoric”, The Journal of American History 88.1 (2001), 75–98

William Lloyd Garrison, “To the Public”, Liberator, 1 January 1831

John L. Thomas, “William Lloyd Garrison”, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 32 vols. (Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1998), V, p. 132

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “The New Revolution”: A Speech before the American Anti-Slavery Society (Boston: Wallcut, 1857)

Don Carlos Seitz, Horace Greeley: Founder of The New York Tribune (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1926).

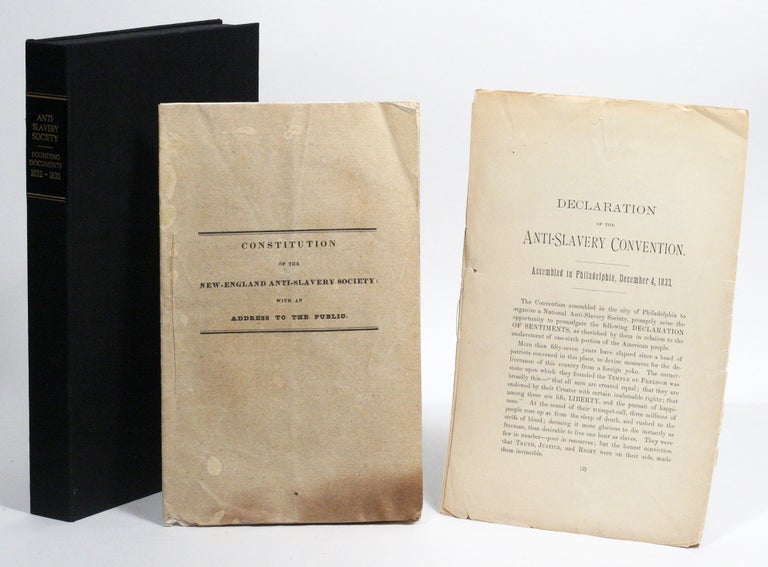

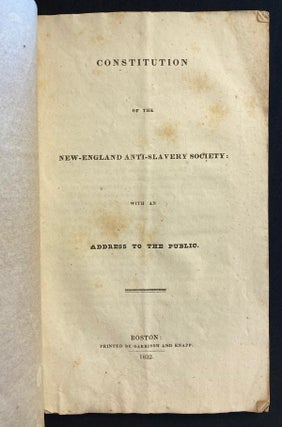

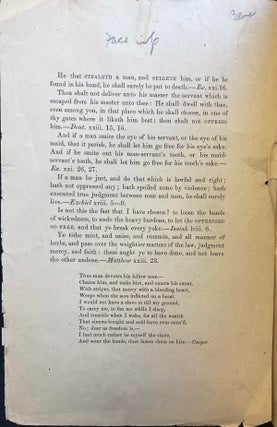

NEW ENGLAND ANTI-SLAVERY SOCIETY. Constitution of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. Boston: Garrison and Knapp, 1832. Octavo, pp. 16, original stitched wrappers. Some toning to wrappers, occasional light foxing and mild creasing.

AMERICAN ANTI-SLAVERY SOCIETY. Declaration of the Anti-Slavery Convention. [Philadelphia]: n.p., [c.1833]. Octavo, pp. 8. Apparently lacking original wrappers (we can find no example with wrappers, but structure/pagination suggests there were wrappers). Stitching lost and now pages all loose (but contained securely in removable mylar). Some light chipping to edges. Both items housed together in custom cloth box.

SCARCE FOUNDATIONAL PUBLICATIONS DOCUMENTING THE ANTI-SLAVERY MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES.

Price: $12,500 .