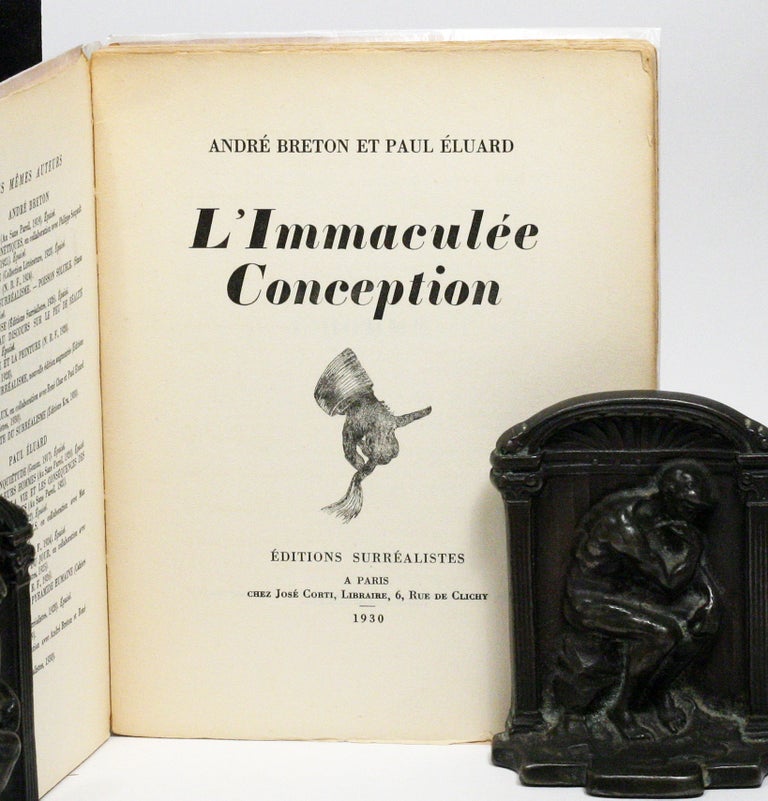

L'Immaculée Conception

“The seriousness with which patriarchal religion regards her makes the Virgin an easy target for the Surrealist’s sense of humour. But her appearing body serves as a metaphor for their own writing bodies—used by them as mediums in their search to unveil the secrets of their own desires—and acts as an appropriate metaphor for the automatic writing project, as an icon for the surprising, modern, automatic text itself.”

– Katharine Conley (p. 608)

FIRST EDITION ASSOCIATION COPY SIGNED AND INSCRIBED BY ANDRÉ BRETON.

Written within the span of only three weeks during the summer of 1930, André Breton and Paul Éluard’s L’Immaculée Conception is a quintessential example of the Surrealist practice of automatic writing. While Surrealism today may at first evoke painters such as René Magritte and Salvador Dalí, Surrealism was demarcated by its founders, namely Breton, as an experiment as much, if not more, in language and literature as the visual arts. Thus, the process of automatic writing which he developed across his lifetime sits at the heart of the first Surrealist Manifesto (1924)—and L’Immaculée Conception represents a pinnacle automatic text executed by two of the major Surrealist vanguards themselves.

In a 1961 interview with Judith Jasmin, Breton maintained that the mission of Surrealism has been the same since 1924, and that Surrealism continues to be defined as:

“automatisme psychique pur, par lequel on se proposait d’exprimer, par écrit ou de tout autre manière, le véritable mécanisme de la pensée. Il s’agissait d’une dicté de la pensée en dehors de tout contrôle—et ceci était très important—de tout contrôle exercé par la raison et en dehors de toute préoccupation esthétique ou morale.” (Breton, 1961)

[pure psychic automation, by which one proposes to express, in writing or any other manner, the true mechanism of thought. It was a dictation of thought beyond any control—and this was very important—any control exercised by reason and beyond any aesthetic or moral concern.]

Barring re-reading and editing, the authors consequently forbade themselves “d’apprecier encours de route le produit de cette activité” [from appreciating, en route, the product of this activity] (Breton, 1961). At times losing “syntactical clarity” and “grammatical intelligibility”, L’Immaculée Conception interrogates what it means to be human and divine and tackles sacred Christian doctrine in a meeting of Breton’s and Éluard’s characteristic wits (Conley, p. 607). Skirting all censorship and demonstrating an intelligence defiantly detached from the human faculties of reason and logic, L’Immaculée Conception reinforces the Surrealist style of surprise and inverted expectation.

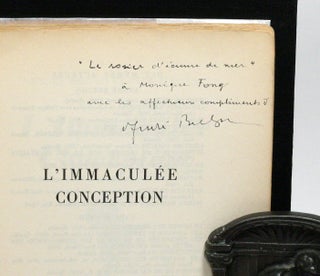

This first edition copy is signed by André Breton to Monique Fong (a.k.a. Monique Fong Wust) with the following inscription:

“‘Le rosier d’écume de mer’ à Monique Fong avec les affectueux compliments d’André Breton”

[“‘The sea-foam rose’ to Monique Font with the affectionate compliments of André Breton”]

In this personalised message, Breton quotes from the penultimate chapter's final section, “L’idée du devenir”:

“Si c’était à recommencer, si c’était à recommencer… Le rosier d’écume de mer est debout à côté de moi dans ce portrait poétiquement définitif” (Breton and Éluard, p. 110)

[If I had to star over, if I had to start over… the sea-foam rose stands at my side in this poetically-definitive portrait.]

A Surrealist writer and intellectual closely connected with many other prominent champions of the movement, Fong Wust first met Breton at a party hosted by Claude Lévi-Strauss and would later maintain a lifelong correspondence with Marcel Duchamp—documenting much of the movement’s aims, ambitions and successes.

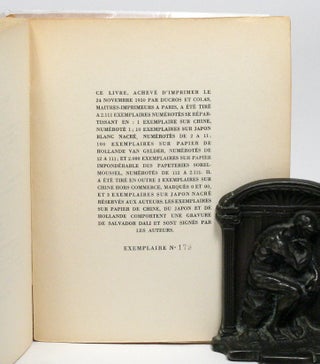

The book is number 179 of 2,000 copies printed on hand-made paper from Sorel-Moussel. Formerly “la véritable capitale du papier” [the true capital of paper], Sorel-Moussel is a village in northern France renown for its paper mills constructed in 1814 and operated by famed printer Firmin Didot, which ceased production in the later half of the twentieth century (Cathelinais, p. 5).

References:

André Breton, “Le sel de la semaine”, interview by Judith Jasmin, Radio-Canada (27 February, 1961),

C. Cathelinais, “L’ancienne papeterie devenue entrepôt abritera une turbine électrique”, Paris-Normande (26 February, 1987)

Katharine Conley, “Writing the Virgin’s Body: Breton and Eluard’s Immaculée Conception”, The French Review 67.4 (1994), 600–608

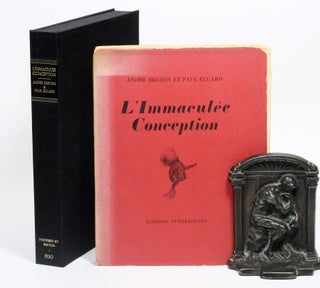

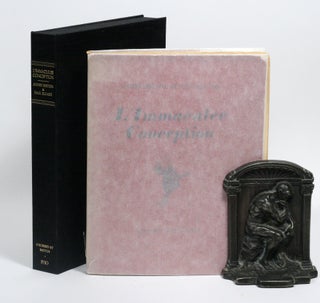

BRETON, ANDRÉ and ÉLUARD, PAUL. L’Immaculée Conception. Paris: Surréalistes, 1930. Quarto (7¼ x 9¼ inch; 184 x 235 mm), number 179 of 2,000 copies printed on papier impondérable hand-made in Sorel-Moussel; pp. 130; originals wrappers, glassine; housed in a custom presentation box. Front wrapper detached (but held snugly under glassine), text block with splits. Fading to spine and perimeter of wrapper.

RARE SIGNED, AND WITH AN INTERESTING ASSOCIATION.

Price: $1,500 .