The Discoverie of Witchcraft

“Reginald Scot's The Discoverie of Witchcraft... stands brightly out amid the darkness of its own and the succeeding age, as a perfectly unique example of sagacity amounting to genius…[for the] clearness of his views and the unwavering steadiness of his leanings to the side of humanity and justice.”

– W. T. Gairdner

“In the sixteenth century, witch hunters scoured Europe in search of those who they believed were dabbling in the dark arts. In 1584, one man [Reginald Scot] spoke out against this toxic mix of superstition, fear, and ignorance. In doing so, he helped shape history and also produced the first book in the English language to present detailed descriptions of magic.”

– David Copperfield

Extremely rare first edition of this far-reaching exposé that provoked King James, inspired Shakespeare and was the first significant work to document the secrets of illusion and the occult. A magnificent copy from the Biblioteca Lindesiana.

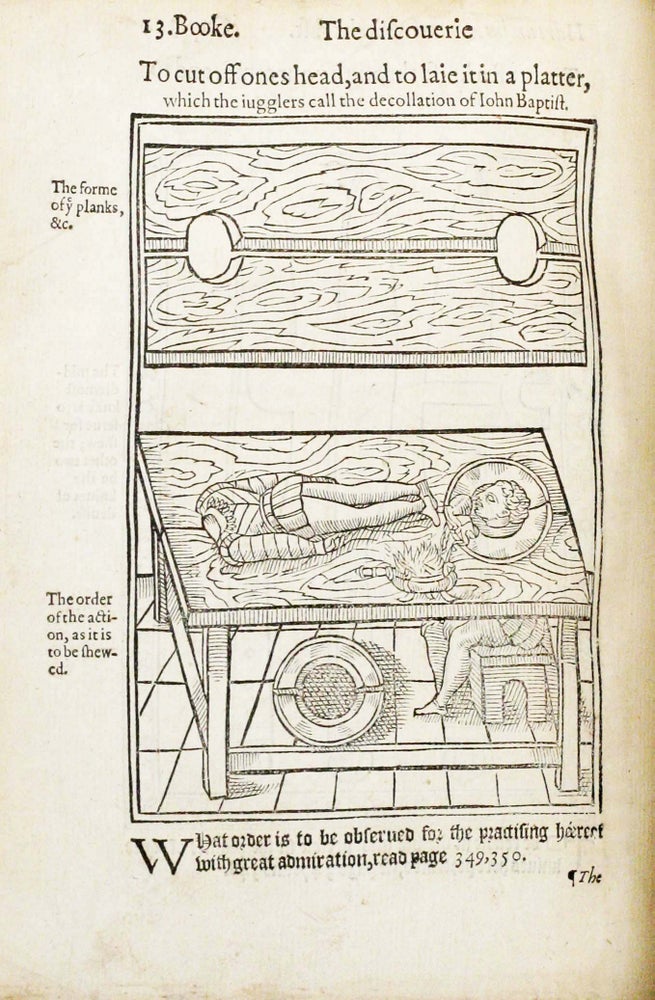

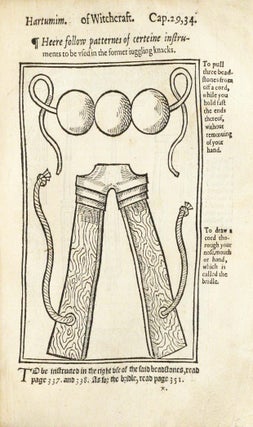

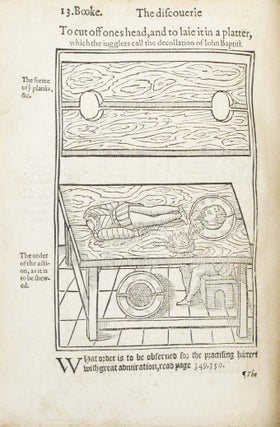

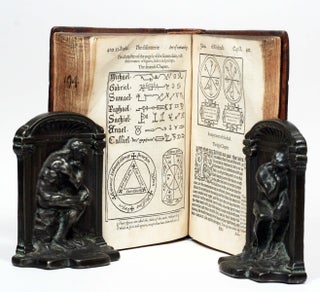

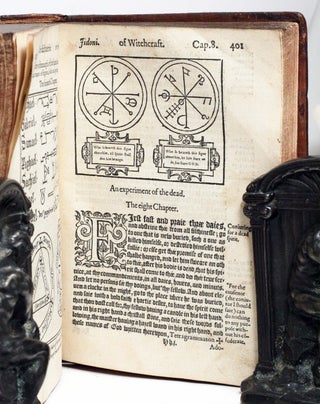

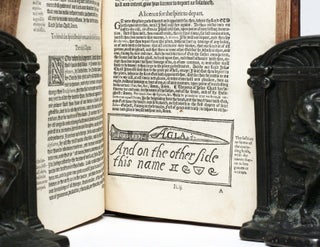

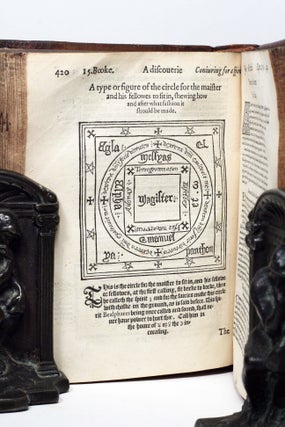

The Discoverie of Witchcraft, written by Reginald Scot in 1584, upended many sixteenth-century beliefs in Britain about witches, superstition, spirits and magic. Scot proves that what was believed to be witchcraft was little more than illusion and delusion. Infuriated by a “ridiculous” 1581 witchcraft trial, Scot in The Discoverie challenges popular beliefs about dark magic, providing diagrams documenting the performance of staged illusions previously ascribed to witchcraft (Reid, “The Discoverie of Witchcraft”). The evidence presented in this pivotal work angered political and religious leaders, gave inspiration to literary masters of his era and contributed a blueprint to future generations of magicians and practitioners of the dark arts.

Consulting hundreds of treatises in Latin and English, studying various scripture and visiting courts of law in districts where witchcraft prosecutions occurred, Scot collected evidence that witchcraft had neither rational nor religious basis. He asserted that the Biblical terms which had been translated as “witch” did not, in their original languages, share the associations ascribed to them in contemporary witchcraft discourse. Thus, one pillar of Scot’s work is the undermining of the scriptural argument for the execution of witches – and further blaming the Catholic Church for encouraging dangerous superstitions.

Scot also contends that spirits cannot take human form nor interact with humans, and consequently that the link between spells cast by so-called witches and any unpleasant events spuriously attributed to witches is entirely coincidental. As set out by one of Scot’s recent biographers David Wootton, Scot explains the witch phenomenon as “resulting out of a particular type of social encounter: old women begging for food or other assistance would curse their neighbours when they were turned away empty handed; if something bad then happened – the death of a child, perhaps – the old woman would be taken to be a witch. Those who confessed to being witches were either deluded or the victims of torture… mere fable and fiction” (Wootton, “Scott [Scot], Reginald”).

Published during the Scientific Revolution, Scot’s lengthy and unrelenting work contributes to a period in which intellectuals were redefining rationality and questioning of old beliefs. Defying both church and state, he labels those who believed in witches as heretics and those who claimed to be witches as mentally ill. Read widely in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, The Discoverie of Witchcraft became an often-cited reference for those who doubted the existence of witchcraft.

James VI, King of Scotland from 1567 to 1625 (and later King of England from 1603), was outraged by Scot’s opinions and penned his objections in his 1597 Daemonologie. The three-book treatise, in which the King holds that witches are not only real but pose a substantial threat to the realm, is a defence of the practice of witchcraft prosecution and a guide for identifying and trying witches. Combined with his writings on a vast array of topics ranging from his views on poetry to his distaste for tobacco, James VI’s response to rising scepticism towards the presence of witches in Britain (chief among them being Scot’s Discoverie) is a central part in his project of text production throughout his reign – second only as an expression of his theology to his commission of the King James Bible, published in 1611.

According to legend, on the occasion of his accession to the English throne in 1603, King James VI and I called for all copies of The Discoverie of Witchcraft to be destroyed. While there is no contemporary evidence to support this story, which first appeared in 1659, The Discoverie was continuously denounced by fellow authors of witchcraft throughout the seventeenth century (Almond, “King James I”). These factors contribute to its scarcity today, especially in complete form.

While Scot set out to disprove the existence of witches, the comprehensive scope and originality of this text allowed it to become a popular resource preserving supernatural practices of this period – incidentally creating an early “how-to” guide for would-be magicians. Shakespeare read The Discoverie of Witchcraft and it is often cited as an inspiration for the witches of Macbeth, Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and the mock trial in King Lear . Thomas Middleton’s The Witch also drew inspiration from Scot’s work. In addition to witchcraft, Scot’s text describes the history of magical illusions and conjuring, topics and themes frequently appearing in Elizabethan literature.

Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft remained a much-used source throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and is one of the few primary sources for the study of witchcraft today. In the modern era, David Copperfield credits Scot with being the first to document the secrets of the conjurers, and has acquired one of the known copies for his museum’s collection, and Copperfield devotes a chapter in his History of Magic to the importance of Scot’s tome.

Provenance:

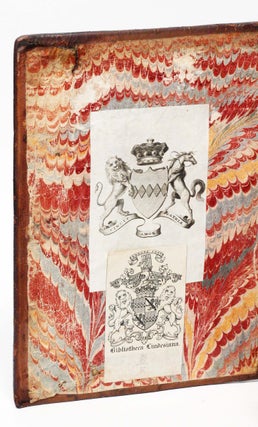

The front pastedown features the Biblioteca Lindesiana bookplate which displays the achievement of arms of the Earls of Crawford. Instituted under this name by Alexander William Lindsay, 25th Earl of Crawford, the Biblioteca Lindesiana built upon centuries-long tradition of book-collecting in the Lindsay family dating back to John Lindsay, Lord Menmuir who served as a trusted ally of James VI’s. What resulted is generally considered to be the finest private library of nineteenth-century Britain.

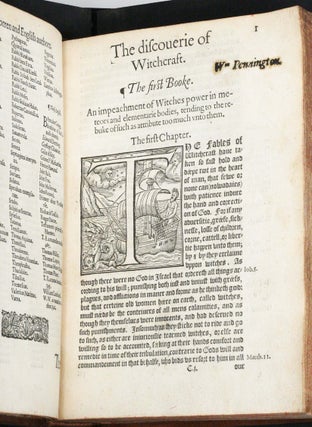

Beneath the Lindesian bookplate is an earlier armorial bookplate of the Pennington family, and the copy also features an early ink stamp on p. 1 of Sir William Pennington, 1st Baronet of Muncaster (“Wm Pennington”). In 1811, the 24th Earl of Crawford married Maria Pennington, daughter of the John Pennington, 1st Baron Muncaster. John Muncaster had no sons and so while his titles passed to his brother, his inheritance, including his book collection, appears to have joined the Lindsays at this time. The Pennington library formed the nucleus for the Biblioteca Lindesiana in the nineteenth century; as William Younger Fletcher, former librarian in the British Museum’s department of printed books, wrote in 1902, “a basis on which the late Earl of Crawford, who was born in 1812, built up the present library, which will be always associated with his memory.” (Fletcher, English Book Collectors, p. 401).

At the turn of the century, the 26th Earl who had helped his father build the Library, made a project of producing catalogues in the numerous volumes they had amassed. Much of the library began to be dispersed at auction within his lifetime, with a number of sales at Sotheby’s in the 1880s and 1920.

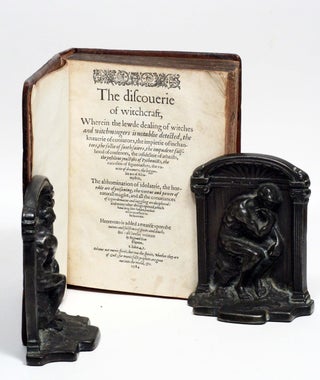

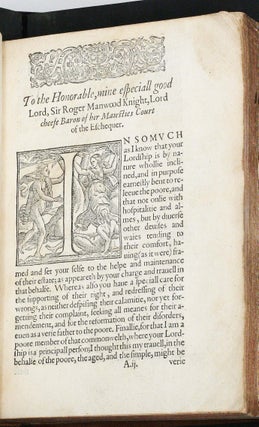

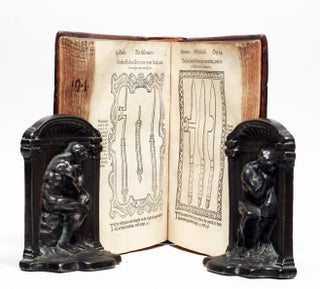

SCOT, REGINALD. The Discoverie of Witchcraft. London: [Henry Denham for] William Brome, 1584. First edition, small 4to (5¾ x 7¾ in), early full mottled calf, with blind tooling, leather spine label, marbled endpapers, speckled edges. Housed in full custom leather box matching binding. Text in roman and black letter with side notes in italic, woodcut head- and tailpieces, historiated and floriated initials, woodcut illustrations, including 4 full-page woodcuts inserted on unnumbered pages between quires Dd and Ee. COMPLETE. With early library docking number (“194”) written on outer text block edge. Nearly invisible repair to joints, evidence of bookplate removed on front free endpaper; very faint dampstaining to early leaves; overall text extraordinarily clean. A remarkably well-preserved copy, with impressive provenance, of a notoriously scarce work.

References:

Almond, Philip C, “King James I and the Burning of Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft: The Invention of a Tradition”, Notes and Queries 56.2 (2009), 209–13

Cohn, Norman, Europe’s Inner Demons (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1933)

Copperfield, David, David Copperfield's History of Magic (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021)

Fletcher, William Younger, English Book Collectors (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Company, 1902)

Gairdner, William Tennant, Insanity: Modern Views as to Its Nature and Treatment (Glasgow: University of Glasgow Press, 1885)

Wootton, David, “Scott [Scot], Reginald”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Price: $150,000 .